Ådalen / Refvelsta / Altuna / Fjärdhundra (prov.) iron meteorite of 7 November 2020 (21:27:04 UT) bolide found near Revelsta, Altuna, Fjärdhundra, Enköping Municipality, Uppsala County, Sweden

Last update: 15 September 2025 (19:15 CEST)

The regmaglypted ‘Ådalen’ (prov.) iron meteorite with its velvety fusion crust. Photo: Andreas Forsberg and Anders Zetterqvist

On 23 February it was announced that on 5 December 2020 a 13.8-kilogram iron meteorite (30 centimeters long) was found by Andreas Forsberg, geologists from Stockholm, about 70 meters away from the location of the mark on a rock boulder and some damaged roots in the ground next to it, which were discovered by geologist Anders Zetterqvist on 16 November. The meteorite must have bounced against the granite boulder and then a flat rock outcrop on the ground, before it became embedded into the soil surrounded by roots and moss next to a birch, 75 ± 1 metres away from the boulder in a south-southwestern direction (azimuth 200°). Forsberg says he saw something metallic ‘shining’ from a mass which was still partly covered by a thin layer of white lichen and was well-embedded in the mossy ground. He removed some of the lichen and immediately knew he had found a meteorite. Since he found it so far from the site of the boulder he was initially unsure whether his find was actually the meteorite they had been looking for or another chance find of a meteorite. Immediately after the find he didn’t dig it out but covered it with moss, went back to his car and called Zetterqvist in Stockholm to ask if he should leave it in-situ so that Zetterqvist could come and see it in-situ as well. Since there was bad weather and just started to drizzle Zetterqvist told Forsberg to dig out ‘the find of his lifetime’ immediately. Forsberg took the meteorite out, wrapped it in some packing material and took it to his apartment where he kept it in a dry environment and took photos of it. Forsberg considers Zetterqvist and himself as the two finders of the meteorite because only their efforts and collaboration made the meteorite find possible. The meteorite mass was larger than expected. The meteorite shows signs (a large crack and impact marks) of its collision with the big granite boulder. It is considered to be the ‘main mass’ of the fall, but other masses (with an approximate total weight equal to that of the found specimen) could not be found in the months after the fall. The meteorite wasn’t handed over to the Swedish Museum of Natural History (on loan for a year) until 14 February 2021 because Forsberg didn’t want to attract the attention of foreign (Latvian and Danish) commercial meteorite hunters who would have brought any finds out of the country. Forsberg wanted the meteorite to be exhibited in the museum and hoped to get a reasonable compensation for his efforts. Landowner Johan Benzelstierna von Engeström reports he learned about the find of the iron meteorite mass on his property from a press release by Eric Stempels on 22 February 2021. The Swedish Museum of Natural History hopes to acquire the meteorite for its collection.

Before, on 17 November Andreas Forsberg (and apparently some days later also the mineralogist Jörgen Langhof, Curator of minerals at the Swedish Royal Museum of Natural History), found ~20 small nickel- and cobalt-containing fragments (1-6 mm) of a meteorite which were thought to have fallen at ~21:27:04 UT on 7 November 2020. The fragments were found with a magnet stick on the mossy ground near the village Ådalen, north of Fjärdhundra, Sweden, about 2.8 kilometers (on the ground) northeast of the calculated end of the bolide’s luminous trail. The fragments were found within a radius of 10 meters around a boulder which was thought to have been hit by a hard object and a metre long pit with damaged tree roots which was supposed to have been caused by the impact of a ‘fist-sized object’. A press release on 26 January by the Uppsala University and the Swedish Royal Museum of Natural History did not mention that it was Forsberg who had found the meteorite fragments. As already said above the site with the roots and the large boulder had been found on 16 November by ‘hobby meteorite hunter’ Anders Zetterqvist, who then told Langhof about it. Since Andreas Forsberg and Anders Zetterqvist initially couldn’t find a larger meteorite mass near the damaged tree roots they thought another (foreign) meteorite searcher had already found and removed it. According to Langhof, after his arrival at the site he searched the area around the pit for merely five minutes while using a neodymium magnet before he found the fragments.

If a very short terrestrial age of the meteorite (which, we believe, must be determined by properly measuring short-lived isotopes of this specimen very soon) confirms its connection to the bolide of 7 September 2020, it will be the first known meteorite fall in Sweden since 1954.

The meteorite at the Naturhistoriska riksmuseet. Video: C. Svahn

The meteorite in a glass case during its first public presentation on ‘Geology Day’ (13 September 2025). Photos: Naturhistoriska riksmuseet

Ownership conflict and Uppsala District Court verdict in December 2022

In April 2021 it was reported that a conflict concerning the ownership of the meteorite had emerged. The owner of the 1000-hectare Refvelsta estate on which the meteorite was found, the 44-year old Count Johan Benzelstierna von Engeström, claims ownership of the meteorite, which he calls ‘Refvelstameteoriten’, and has taken legal action. He claims the ‘Allemansrätten’, the Swedish ‘Right of public access’, does not apply in the case of a meteorite find, because according to him the removal of objects of economic value from someone’s property is not covered by this law. Benzelstierna von Engeström claims he does not want to sell the meteorite but instead wants to see it on exhibition in a Swedish museum. He claims he does not want to give up ownership of the meteorite. By 24 October 2021 the dispute could not be settled and would have to be decided in court. The main hearing at the district court in Uppsala began on 21 November 2022 and the verdict was given on the 20 December 2022 around 2 p.m. : press release (20 December 2022) / English (automatic translation). The meteorite belongs to the two finders, Anders Zetterqvist und Andreas Forsberg, because after its fall it did not become a part of the property it fell on (”Inte en del av fastigheten” (“Not part of the property”)). The court states: “The district court has considered that a recently fallen meteorite has no permanent connection to the earth or the property and cannot be expected to remain on the property for a long time.” … “a recently fallen meteorite is not part of the property on which it has landed.” … “A recently fallen meteorite cannot be considered to constitute such a natural product that is covered by public rights. On the other hand, the public right is important in that it gives everyone a right to look for meteorites on someone else’s land, as long as the property is not damaged. This applies regardless of a meteorite’s value” … “In order for someone to become the owner of moveable property that has no owner, the property must be taken into possession. The property owner cannot be deemed to have obtained possession of the meteorite simply because it has landed on his property. Ownership goes instead to the person who found the meteorite and, in connection with that, took possession of it. Since the property owner has not become the owner of the meteorite, the company’s claim for better rights has been rejected.” Thus the meteorite keeps its state as “var lös egendom utan ägare” (“movable property without an owner”) until a finder takes possession of it. In January 2023 Landowner Johan Benzelstierna von Engeström appealed the court’s judgement. There is no explicit Swedish law concerning meteorite finds in Sweden. As confirmed by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency it is however apparently forbidden by the Criminal Code to remove terrestrial stones, gravel or peat from someone’s property without permission.

The finders, Anders Zetterqvist und Andreas Forsberg, who referred to the ‘Allemansrätten’ claimed that found meteorites, as ‘non-terrestrial objects’, have traditionally belonged to the finders. The Swedish Museum of Natural History, where the meteorite is currently curated had commissioned a law firm to conduct a legal investigation on the matter.

On 23 February 2021 it was reported that Johan Benzelstierna von Engeström has planned to erect an obelisk with a meteorite replica on top as a meteorite memorial at the fall site and to turn it into a tourist attraction.

Verdict of Svea Court of Appeal (21 March 2024)

On 21 March 2024 the Svea Court of Appeal ruled in its Judgment in case of better right to meteorite / (original text of the verdict in Swedish) that the meteorite is considered “part of immovable property just like other stones, even though it may intuitively feel like a meteorite is something foreign to the earth” because it contains “substances that are already present in the earth’s surface and which, by their nature and character, cannot easily be separated from what is normally to be regarded as real property as part of the earth”. Judge Robert Green ruled that the ‘Allemansrätten’, the Swedish Right of public access, “does not give everyone the right to take a meteorite from another person’s land” unless there is a clear agreement between landowner and finder, which could not be proven in this specific case. One of the members of the Svea Court of Appeal disagreed and wanted to confirm the original Uppsala District Court’s verdict. The two finders had the right to appeal the verdict in front of the Supreme Court before 18 April 2024. On 18 April is was reported that in the evening of 17 April 2024 Anders Zetterqvist and Andreas Forsberg decided to appeal to the Supreme Court, which can grant leave to appeal and take up the case, or deny the appeal and thus confirm the judgment of the Svea Court of Appeal. Several Swedish media reports in Sweden in late October 2024 in Sindicate that the Supreme Court has decided to take up the case. The court case is unique in Swedish legal history. The 46-year old landowner Johan Benzelstierna von Engeström would like to give the meteorite to a museum on permanent loan during his lifetime.

Verdict of the Swedish Supreme Court (Högsta Domstolen) (19 August 2025)

In its final judgement, published on 19 August 2025, the Swedish Supreme Court (Högsta Domstolen) upheld the District Court’s judgement from December 2022. The two finders Anders Zetterqvist and Andreas Forsberg can keep the meteorite because after its fall it did not immediately become a part of the ground or property it fell on and thus kept its status as an ownerless ‘movable object’ or ‘movable property’, which basically can be acquired by picking it up for the first time and thus taking it into one’s possession. The finder thus becomes the first owner of the extraterrestrial object. Justice Councillor Anders Eka dissented and wanted to uphold the Court of Appeal’s judgment but she has been outvoted by a majority. The Supreme Court judgement of case T 3007-24 can be seen as a precedential case for how to deal with future meteorite falls. On 19 August 2025 the Swedish Supreme Court published the following text excerpt (here as automatic translation) as part of their judgement (see the PDF of the full text in Swedish HERE): “An assessment of whether the owner of the property on which a meteorite is located has ownership rights to it should be based on the regulation that determines what constitutes real property. As has been stated, real property is land or such things that, according to the special regulation on this, constitute property accessories. What constitutes real property is thus stated positively. A meteorite cannot be considered a property accessory. In order for a meteorite to be seen as part of the real property, it is required that it can be considered to constitute a component of the earth. What constitutes real property should be related to the property and typically be of a permanent nature (cf. p. 12). The concept of soil includes, among other things, clay, stone and gravel. Material of the kind found on a property is thus normally part of the real property. However, this is not necessarily the case if it is clear that the material does not belong to the property on which it is located or if the material can otherwise be traced to another owner. Decisive for the assessment of whether a meteorite constitutes part of the real property should be that a meteorite is unique in that it comes from space and because of its material and properties. It differs from rocks and other such materials that constitute components of real property. Although a layperson cannot always distinguish a meteorite from a rock, it can, in any case, be determined after sampling whether an object is a meteorite or not. Overall, this means that the starting point should be that a meteorite does not constitute a component of the real property on which it has landed. That now said does not rule out that a meteorite when it has elapsed a certain time can become an integral part of the earth and on that foundation should be seen as a part of the fixed property on which it is. It does not exclude that one meteorite that has just fallen down immediately may be so attached to the earth that it may be considered to have been integrated with it. The exterior observable the conditions – which can thus change over time – have significance when the assessment (cf. p. 14). It is inevitable that boundary issues can arise. However, the difficulties should not be exaggerated and they should not be given any decision importance for how a meteorite should be judged legally (cf. p. 13). In summary, a meteorite should be regarded as loose property if it has not been integrated with the fixed property. A finder can acquire ownership of a meteorite that constitutes loose property by taking the one in its possession (see p. 23).The assessment in this case it appears from the investigation that the meteorite was found in a moss covered area on a mountain hob on the property in question. It had recently fallen and low easily available. It had thus not been integrated with the earth. Against this background, the meteorite has been movable property. This also applies if the meteorite has a not insignificant economic value. It has not been alleged that the property owner or someone who worked for Refvelsta had found it or even be sure there was a meteorite on the property. The meteorite cannot, under such conditions, be considered to have been in the property owner’s or Refvelsta’s possession when it was found (cf. p. 22). Since it – as far as it has come out of what has been made in the case – was not owned by anyone nor were in someone’s possession had the finders right to take the meteorite with them. On that basis, they thereby acquired ownership of it (cf. p. 23). The above means that what Refvelsta has invoked in support of its claim does not mean that the company has a better right to the meteorite than A.F. and A.Z. In view of the above, the Court of Appeal’s judgment shall be amended and the District Court’s judgment shall be upheld both on the merits and in terms of legal costs. The Court of Appeal’s judgment shall also be amended with regard to the legal costs there. A.F. and A.Z. are therefore entitled to compensation for their legal costs in the Supreme Court.”

“Det är fantastiskt, fantastiskt skönt. Jag är väldigt lättad. Efter fem år är det äntligen över och vi har vunnit” (“It’s fantastic, fantastically nice. I’m very relieved. After five years it’s finally over and we’ve won”) [Anders Zetterqvist on 19 August 2025]

The Swedish Natural History Museum now hopes to be able to acquire the meteorite from the finders. Discussions between finders and Natural History Museum about an aquisition of the meteorite will start soon. Andreas Forsberg and Anders Zetterqvist are reportedly willing to offer the meteorite, which is currently only borrowed, to the museum at a price which it can afford. Only after an aquisition of the meteorite by the museum the scientific analysis and classification can begin. On 13 September 2025, ‘Geology Day’, the meteorite was put on public display at the museum for the first time.

Documentary film METEORITEN (2024)

Directors Johan Palmgren and Isabel Andersson have made the 59-minute documentary film Meteoriten about this meteorite fall and the following legal dispute. The film primarily covers the events until the Uppsala District Court verdict in December 2022. The film was shown during the TEMPO film festival in Stockholm (4-10 March 2024) and first published online (VIEW) at 02.00 CEST on 26 May 2024 by SVT. The film was broadcast on SVT1 on 28 May 2024 (20.00-21.00 CEST).

The First Instrumentally Documented Fall of an Iron Meteorite: Orbit and Possible Origin

Ihor Kyrylenko, Oleksiy Golubov, Ivan Slyusarev, Jaakko Visuri, Maria Gritsevich, Yurij N. Krugly, Irina Belskaya, and Vasilij G. Shevchenko

The Astrophysical Journal, Volume 953, Number 1

Published: 28 July 2023

Moilanen J. Gritsevich M.

LPSC 2022 abstract [#2933]“We study is it possible that a 14 kg iron meteorite can jump 75 meters after hitting on a granite boulder.”

Possible Origin of the First Iron Meteorite with an Instrumentally Documented Fall

Kyrylenko I. Golubov O. Slyusarev I. Visuri J. Gritsevich M. et al.

LPSC 2022 abstract [#2655]“We determine the orbit of the first iron meteoroid with instrumentally recorded fall, simulate its past orbital evolution and origin in the main asteroid belt.”

A Spatial Heat Map for the 7 November 2020 Iron Meteorite Fall

Moilanen J., Gritsevich M.

84th Annual Meeting of The Meteoritical Society 2021 (abstract # 6252)

“On the difference between density and mass distribution per surface area heat maps made from dark flight Monte Carlo (DFMC) simulations. Using simulations for a recent, but still unclassified, iron meteorite fall in Sweden as an example.”

The meteorite ‘in situ’ on 5 December 2020. Photo: Andreas Forsberg

Johan Benzelstierna von Engeström pointing at the exact find location of the meteorite next to a birch tree. Image: SVT

Andreas Forsberg and Anders Zetterqvist presenting the meteorite. Photo: Andreas Forsberg and Anders Zetterqvist

Other side of the meteorite with impact marks and damage from hitting the boulder. Image: SVT

Boulder with impact mark. Image: SVT

The probable path of the bouncing meteorite mass. Photo: Anders Zetterqvist

The impact site on the granite boulder. The impact mark on the southwestern slope (45 – 50° from the vertical) of the boulder is 22 cm long and 9 cm wide. Image: SVT

Three fragments. Photo: Naturhistoriska riksmuseet

Photo: Naturhistoriska riksmuseet

Press

Rättstvist stoppar forskning om meteoriten (Forskning & Framsteg, 28 January 2025, in English, automatic translation

Meteoriten i Enköping: Den stenhårda striden (Filter #82, 27 September 2021)

automatic translation

LINK Naturhistoriska riksmuseet – Press release (23 February 2021)

LINK Naturhistoriska riksmuseet (23 February 2021)

LINK (23 February 2021)

LINK (Uppsala universitet, 26 January 2021)

LINK (Naturhistoriska riksmuseet, 26 January 2021)

Lantbrukets Affärstidning (23 April 2021)

SVT (24 October 2021)

The bolide

The preatmospheric orbit

Trajectory calculations (Norsk meteornettverk)

The preatmospheric orbit (orbit elements: perihelion distance: 0.898 AU, eccentricity: 0.546, inclination: 15.0°, knot length: 225.6°, perihelion argument: 222.7°, mean anomaly: 348.8°

Video recordings of the bolide

Video from Larvik, Norway. Video: Norsk meteornettverk

Bolide (00:03-) and detonation booms (00:33-). Video: biancoczt1 (16 November 2020)

Bolide (00:03-) and detonation booms (00:35-). Video: biancoczt1 (16 November 2020)

Video from Tampere, Finland. Video: kakuure

Video from Merikarvia, Finland

Video from Västerås, Schweden. Video: Cadde News

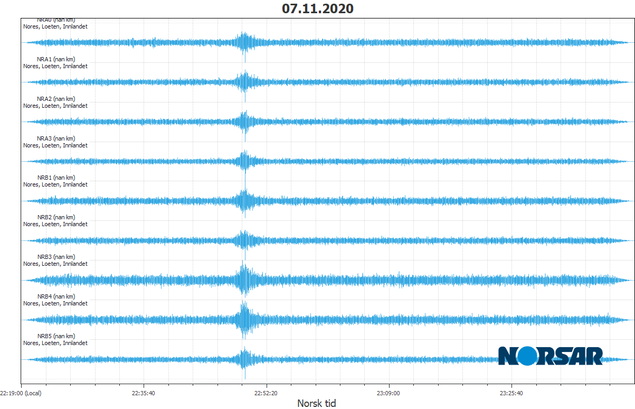

NORSAR’s infrasound station in Løten registered clear signales in an easterly direction (azimuth 111) 22:48 (21:48 GMT) 2020